Part III: Life At The Station

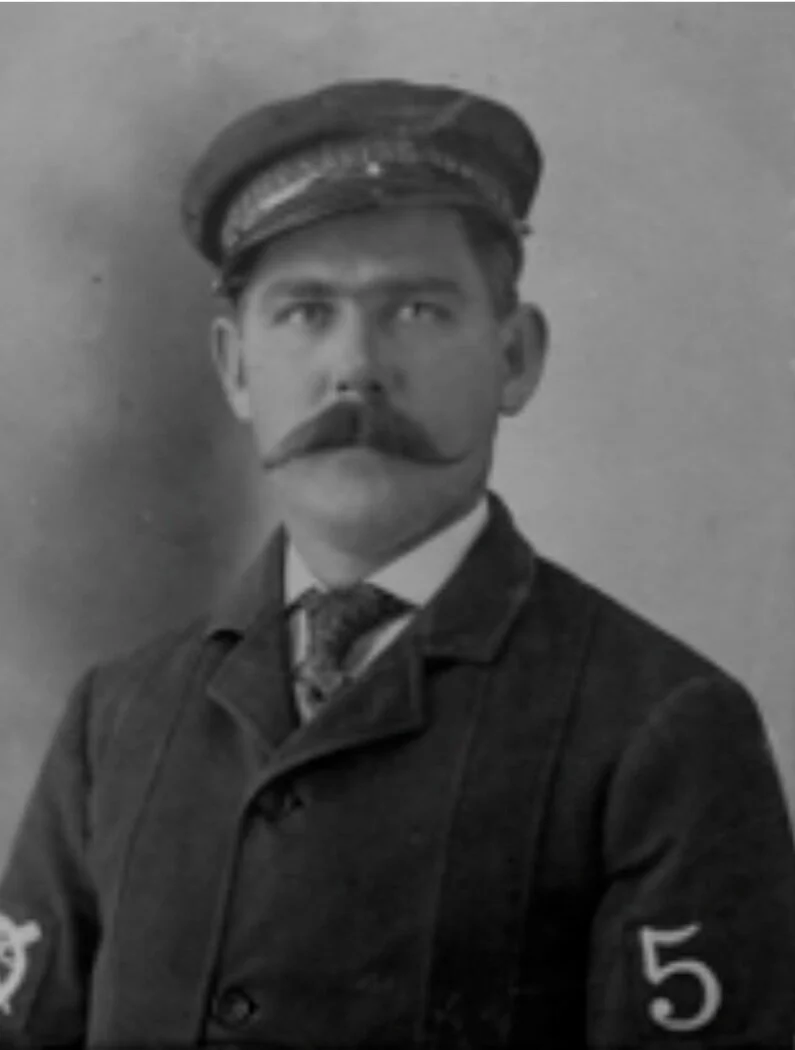

Portrait of Surfman No. 5

Collection of Tom McCabe

Someone once noted that existence at a Life-Saving Service Station could best be summarized as endless days of boredom interrupted by moments of sheer terror. While such a statement may have been a bit overdrawn, it was not without merit. The job was at times a dangerous occupation but to be proficient in those moments of danger one had to submit to the boredom of endless drill and practice. Superintendent Kimball early realized, following his study of the volunteer attempts at lifesaving, that a system lacking in order, discipline, and most importantly, drill, was the primary reason a volunteer approach did not work. Once he had gained the support of the U.S. Congress and the attention of the American public he set out to create a lifesaving system that would become the pride of the nation.

Kimball’s little manual, “Regulations for the Government of the Life-Saving Service of the United States” made it abundantly clear to all who accepted appointment to the Service that he expected all stations to be run as “tight ships”. Not only did this unflinching attitude create espirit de corps among crews but equally produced persons who were competent in their duties, brave in the face of danger, and attentive to cleanliness, order, and the maintenance of the equipment they were to use in the performance of their duties.

While the size of the crew assigned to each station sometimes varied according to local conditions, it generally consisted of a Keeper, who was the person in command, and six Surfmen. The Surfmen were numbered one through six and displayed their number on the sleeve of their uniforms. A Surfman’s number not only noted his seniority, but also noted his overall competency and determined the specific jobs to be done by that individual during emergencies. The Keeper was chosen based upon his demonstrated competency and his ability to be a leader, after having risen through the ranks of the Surfmen.

Part of the endless boredom experienced at the station was the need for continuous watch from the station tower during daylight hours and the requirement to patrol along the surf during hours of darkness. Watch during daylight consisted of the crew taking turns standing watch in the station tower, telescope in hand, constantly scanning the ocean before them (and the bay behind them if such existed), looking for mariners in distress. Standing was the operative word in this case since Kimball permitted no stools or chairs in the tower because he did not wish the Surfman on duty to become too comfortable. Additionally, the tower was provided with a bell that was to be rung at intervals so the Keeper below would know the Surfman was awake. By locating stations every six to eight miles along the coast, this watch strategy provided a visual interlocking system along the entire coast. Should the one on watch observe any problem; it was his duty to summon the Keeper by ringing the bell so a decision could be made as to whether assistance was needed.

Surfman’s brass badge or token

Once night descended the Surfmen began assigned foot patrols along the beach. Again, station positioning along the coast resulted in interlocking patrols if each station sent a Surfman out in each direction. If all stations were consistent in their assignments this resulted in each Surfman being required to walk a three to four mile patrol for a round trip of six to eight miles. This was often a difficult and strenuous task especially when storm conditions prevailed.

The Surfmen were supplied with appropriate clothing and boots, a lantern, a Coston Signal Kit, and a Surfman’s brass badge or token on which was noted his station and number. The Coston Signal was not unlike today’s flare gun and was to be used as a warning device when necessary. It was the duty of the Surfman to constantly look seaward as he walked, looking for ships in distress. If he saw a vessel that was headed into danger he fired a Coston Signal in the hope the master of the ship would realize his error and turn seaward. If the vessel was already in the process of foundering, the signal was deployed to indicate they had been discovered and help was on the way. In such a circumstance it was critical that the patrolman take accurate note of the circumstances and quickly return to the station to apprise the Keeper of the details. Accurate information was essential to allow the Keeper to decide what apparatus should be transported to the scene.

Should the patrolman observe no problems on his section of beach he was required to proceed until he met his fellow patrolman from the next station. The two shared any information resulting from their respective patrols and, before departing for their return, they also exchanged Surfman’s Badges. Taking the other Surfman’s Badge back to the Keeper was unquestionable proof the full patrol had been walked. If the Surfman did not meet up with the patrolman from the next station, he was expected to continue on since this was a likely indication the other Surfman was in difficulty or had come upon a vessel in distress.

The Life-Saving Regulations were specific that each day of the week, excluding Sunday, have some type of drill activity that was to take place. Before describing the drills prescribed it will be well to discuss the rescue equipment that was housed in each station. After much research (which in itself is a fascinating topic since Kimball was bombarded with many ideas for surf rescue, some rather eccentric), it was determined each station would house three types of rescue equipment: the Apparatus or Surf Cart with Lyle Gun and Breeches Buoy; the Pulling Surfboat; and the Life Car. Each piece of equipment was designed for a particular circumstance and it was always an important judgment call on the part of the Keeper as to which should be employed.

The Apparatus Cart or Surf Cart with its Lyle Gun and Breeches Buoy was the equipment of choice and was also the one that required the most skill. The cart, when fully loaded, weighed over 1000 pounds and was pulled to the scene of the wreck by the six Surfmen in shoulder harness, a feat in itself in foul weather. Essentially, the cart provided everything needed to employ the Lyle Gun for rescue of those in peril. The gun was a small brass cannon that fired a seventeen pound projectile to which was affixed a “whipline”, which was a small rope. It was the duty of the Keeper to accurately aim the gun so the projectile, when fired, would go over the rigging of the vessel, entangling the whipline in the process. It was then the task of those on board the ship to climb the rigging, retrieve the line, and use it to haul out a larger hawser, which was made fast to the mast. Simultaneously, the Surfmen were burying a sand anchor to which they attached the other end of the hawser. When the slack was pulled out, the hawser provided the means to send the Breeches Buoy out to the vessel. The Breeches Buoy was nothing more than a life ring containing a pair of canvas shorts into which an individual could sit and be pulled to shore.

Since the use of this equipment required skill and precision timing, the drill was held twice a week, Mondays and Thursdays. Each station had a practice pole, which was a substitute ship’s mast. The Apparatus Cart was rolled out and the rescue technique was accomplished by the crew using the practice pole as a substitute vessel. Kimball’s expectation was that the exercise be fully accomplished within five minutes if the crew was to be deemed proficient.

Each Tuesday the Pulling Surfboat was used in drill. A Pulling Surfboat was approximately 26 feet in length, double-ended, clinker built in a manner to be light yet flexible and strong. It was rowed or “pulled” by the six Surfmen, using long oars or sweeps, and was steered by the Keeper employing a steering sweep in the stern. Built with a watertight deck and scuppers, and having buoyancy compartments below deck, it was virtually unsinkable but was capable of capsizing. It was pulled to the scene of the wreck on a wide-wheeled cart, the boat and cart weighing over 2000 pounds. Amazingly, it was also originally pulled to the scene of the wreck by the crew in harness. This was soon discontinued since the effort was so strenuous it left the men exhausted before they could commence the rescue. Soon each station maintained a team of horses for this purpose. The cart was designed to allow the bow of the boat to be lowered at the edge of the surf. The Surfmen then launched through the waves, rowing to the wreck and removing those onboard five or six at a time. They returned with those rescued and rode the waves back to the beach, a skill that was not only exhausting but emotionally demanding, especially in foul weather. The Surfboat was used whenever weather conditions or distance from shore prohibited employing the Breeches Buoy.

The Tuesday drill required the crew to take the Surfboat out of the station boatroom, regardless of weather, launch it through the surf, and row to sea for at least 30 minutes. They were also required to conduct a capsize drill. This entailed the intentional capsizing of the boat, then righting it, and returning to shore. It was said that the only time when Surfboat drill was omitted was “when the ocean was frozen over” which, of course, was not very often!

Lifecar drill using the surfboat

From time-to-time the crew was required to practice with the Lifecar, utilizing the Surfboat in the process. The Lifecar was cumbersome and saw little use, especially in the later years. The Lifecar was a small metal boat with a watertight canopy and hatch that could be sent out via the same line used for the Breeches Buoy. Its purpose was to rescue injured seamen, small children, the elderly or frail, or any other person that might be onboard a stricken vessel whose condition was such they might not survive a ride in the Breeches Buoy. Up to five persons could be rescued simultaneously utilizing the Lifecar. The Lifecar was not without its dangers; a limited air supply and claustrophobic conditions made the Lifecar a rescue to be remembered. When drilling with this equipment the Surfboat was sent out to sea with a portion of the crew to serve as the vessel in distress and the remaining crew working on the beach to pull the car back and forth.

Wednesdays were reserved for drill using Morse Code and semaphore flags to communicate. They also practiced “flag hoists”, the system ships used to communicate at sea. These skills were necessary to communicate with each other on the beach during stormy conditions as well as with vessels in distress.

Fridays were devoted to first aid practice and to the equivalent of today’s CPR which the manual referred to as “restoring the apparently drowned”. Saturdays were set aside for cleaning and maintenance so that the station was “shipshape” for Sunday’s day of rest.

It was expected that the Station Logbook would reveal daily entries documenting that the prescribed drills had been accomplished. If for any reason the drill was not done, a very good reason for such was to be noted. The Logbook also posted the daily patrol schedule and weather conditions along with note of any assistance rendered by the crew. Regular, often unannounced, inspections were done by Kimball’s District Superintendents and all was expected to be in order upon inspection. If deficiencies were noted, the source of the problem was determined and promptly corrected. This could include dismissal from the service for those responsible. As might be expected, Kimball’s “tight ship” resulted in a proud and skilled institution that was held in high esteem by the U.S. population and whose members respected and admired their leader.

<- Go To Part 2 Go To Part 4 ->